|

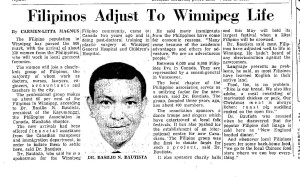

Mujer de la clase rica

(Woman of the upper class)

Philippines, circa 1875

Photographer: Francisco van Camp

Ref: SK06745-04 |

I am not going to lie. It is incredibly challenging to conduct genealogical research in Winnipeg on my Irish-Spanish-Mexican-Chinese-Filipino ancestry. It would be a dream for me to arrive at the archives in any one of these countries in Europe and Asia to dig through church records and legal documents that may still be available. Sadly, until that dream comes true, I must rely on online secondary sources. So, as I post what I learn about my family history, I must caution that everything I share here is entirely open to interpretation. With that said, I’m going to take a particularly risqué approach to this week’s blog post.

I want to know what could have possibly brought my ancestors, Don Felix Berenguer de Marquina (the Irish-Spaniard) and Doña Demitria Lindo Sumulong (the Chinese mestiza) together in the late 1780s. Did the concept of love exist then?

The cynical tone I take towards their union is not necessarily a commentary on love in general, but the circumstances of the time that may have initially brought them together. The information I have gathered for these last few blog posts are based on my distant cousin’s family history website, The Official Sauza-Berenguer de MarquinaWebsite. The site describes Don Felix as follows:

Señor Felix Berenger de Marquina y Fitzgerald (1736, Alicante, Spain – 10 October 1826, Alicante, Spain) was married to Maria Ansoategui y Barron in 1758, but he had relationship to Doña Demetria Sumulong y Lindo (1772-01 February 1814, Cagsawa, Albay, Philippines) also known as Metyang. Señor Felix and Demetria had one daughter. She was Doña Ysabel Berenguer de Marquina y Sumulong (19 November 1790, Cagsawa, Albay, Philippines – 30 Januar 1900, Banwa, Batan, Aklan, Philippines) also known as Abe. She was baptized on 25 December 1790 at a Franciscan church in Cagsawa, Albay, Philippines. Though she was illegitimate by birth, her mother Metyang who was 18 years old by that time never took the plan to abort her instead she was born in the vast greenfields of Cagsawa, Albay, Philippines. Abe had a unique and interesting ancestries both paternal and maternal. She was the 23 great granddaughter of Nest Ferch Rhys, the Princess of Deuhebarth and of Gerald de Windsor. Señor Felix was the Viceroy of New Spain 1800 – 1803.

I read this paragraph as though it was written cautiously. Words like “illegitimate by birth” and “abort” are explosive terms among conservative Catholics – whether they live in the Philippines today or centuries ago. There is no mention of a courtship, but a “relationship” between our ancestors. There is nothing said about his infidelity to his Spanish wife or if he fathered other children with other women. Perhaps these are modern concepts that I am placing to a different time, but I can’t help but wonder. What impressions did the Philippines have on Don Felix? What brought him to eventually meet Doña Demetria?

Wikipilipinas: hip ‘n freePhilippine Encyclopedia (2011) says that Don Felix lived in Binondo, Manila as the Philippine Governor-General from 1788 to 1793. Binondo was an influential Chinese settlement in the Philippines. As Governor-General, he was appointed by the Viceroy of New Spain to represent the Spanish King on the colony. He held executive colonial powers as well as incredible political influence in this position. Within his exclusive circle, he was acquainted with Manila’s most affluent which included Chinese mestizo families who dominated the local economy.

According to historian, E. Wickberg, the Chinese mestizo played a strong role in Spain’s colonization of the Philippines. He states:

Soon after the Spaniards arrived, the Chinese moved into an important economic position. Chinese merchants carried on a rich trade between Manila and the China coast and distributed the imports from China into the area of Central Luzon, to the immediate north of Manila. Chinese established themselves at or near Spanish settlement, serving them in various ways: as provisioners of food, as retail traders, as artisans. Because the Chinese quickly monopolized such activities, the Spanish came to believe their services indispensable. (Wickberg, p.67)

Don Felix arrived in Binondo to an already established Catholic, Chinese mestizo community. He likely noted that the Chinese mestizoappeared more Spanish than they did ethnically Chinese. For example, they dressed and worshiped essentially the same Hispanic way. So, when Don Felix came to meet Doña Demitria, he was not acquainted by her Chinese family name of Li, but her Spanish Catholic family name of Lindo meaning “beauty.”

Doña Demitria’s maternal lineage can be traced to southern Fujian in China. Her mother, Maria Andrea Lindo, was raised in Binondo, where she likely worked in the family’s successful clothing and food business. Her mother later married her father, Fortunato Sumulong, an ethnic Filipino farmer. Living in Binondo as a Chinese mestiza family meant that they were afforded certain privileges. They enjoyed access to land, discounts to colonial tribute, as well as limited self-governing privileges. The Chinese mestizo held degrees of wealth and influence.

My research would seem to imply that Doña Demitria was not a victim of colonization. At a time when Spanish authorities (both religious and secular) raped and abused local indigenous women to exert their colonial power, Chinese mestizos maintained certain freedoms and privileges under the same colonizer. The colonized body of the indigenous Filipino was not the same as the Chinese mestizo. Whereas the former made up the vast peasantry, the latter represented networks of wealth. I believe Spanish authorities had political balances to achieve and networks to maintain to legitimize their role. I imagine it would be beneficial to maintain the existing status quo with favorable relations among influential Chinese mestizos.

The Chinese mestizaduring the Spanish colonial period (1521-1898) would have been expected to play her gendered role in society. According to historian Mina Roces, women in the Philippines were considered the man’s help. She was relegated to the home and had little opportunity to venture outside publicly unless it was to attend church (Roces, p.164). As a member of the elite, Doña Demitria’s outings were likely supervised and limited. I would guess then that the Governor-General’s intentions towards her were not made in secret (whatever those intentions were).

Could love have found its way into their “relationship”? I hesitate to say. What I do know is that the balance of power between my two ancestors is not easily defined. The dynamic between older man and younger woman as well as colonizer and colonized can mean different things given the circumstances. He was a ruler outnumbered by an established and wealthy ethnic community. He was likely without contact with his wife (let alone of Spanish women in general). Chinese mestizos could have served to solidify political networks or social voids for him. Really, your guess is as good as mine.

Before I conclude, I want to share one of colonial Philippines iconic images. In around 1875, Dutch photographer Francisco van Camp photographed a Filipina Chinese mestiza. The portrait entitled, Mujer de la clase rica (Woman of the upper class) captures her thick flowing hair, exotic physical features, and elegant dress. She epitomizes both nobility and simplicity simultaneously. She is beautiful (if not stunning). The portrait suggests that her social class and telling mixed features have afforded her the unique luxury of beauty. Maybe Doña Demetria resembled her likeness only a century ago? Who would Don Felix be, as the most powerful authority on the colony, to let her walk away?

Sources:

E. Wickberg. (1964) “The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine History,” The Journal of Southeast Asian History 5.1: 62-100.

Mina Roces. (2002) “Women in Philippine Politics and Society” in Hazel M. McFerson, ed. Mixed Blessing: the impact of the American colonial experience on politics and society in the Philippines. Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 159-175.